What is Webpack

#

Webpack is a module bundler. Webpack can take care of bundling alongside a separate task runner. However, the line between bundler and task runner has become blurred thanks to community-developed webpack plugins. Sometimes these plugins are used to perform tasks that are usually done outside of webpack, such as cleaning the build directory or deploying the build although you can defer these tasks outside of webpack.

React, and Hot Module Replacement (HMR) helped to popularize webpack and led to its usage in other environments, such as Ruby on Rails↗. Despite its name, webpack is not limited to the web alone. It can bundle with other targets as well, as discussed in the Build Targets chapter.

Webpack relies on modules

#

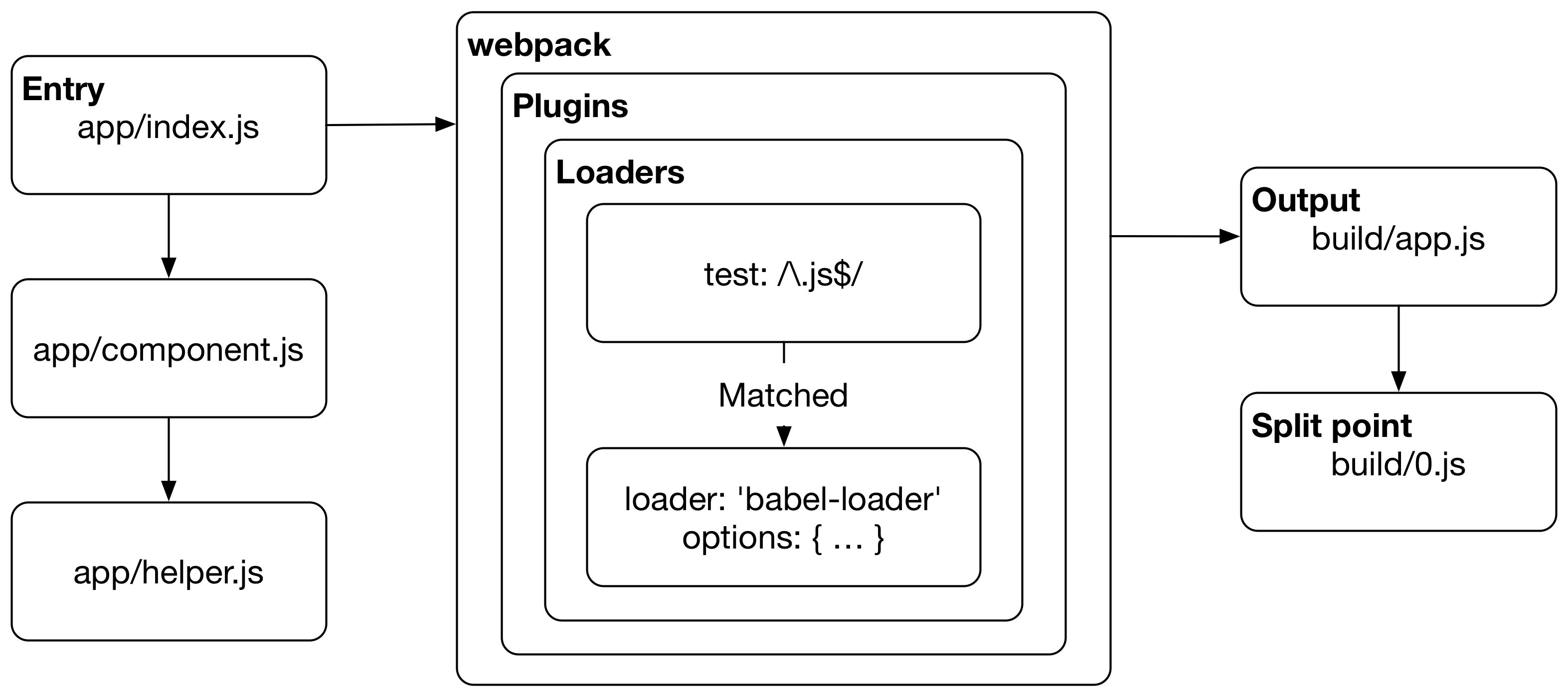

The smallest project you can bundle with webpack consists of input and output. The bundling process begins from user-defined entries. Entries themselves are modules and can point to other modules through imports.

When you bundle a project using webpack, it traverses the imports, constructing a dependency graph of the project and then generates output based on the configuration. Additionally, it’s possible to define split points to create separate bundles within the project code itself.

Internally webpack manages the bundling process using what’s called chunks and the term often comes up in webpack related documentation. Chunks are smaller pieces of code that are included in the bundles seen in webpack output.

Webpack supports ES2015, CommonJS, MJS, and AMD module formats out of the box. There’s also support for WebAssembly↗, a new way of running low-level code in the browser. The loader mechanism works for CSS as well, with @import and url() support through css-loader. You can find plugins for specific tasks, such as minification, internationalization, HMR, and so on.

require, import) between files. Webpack statically traverses these without executing the source to generate the graph it needs to create bundles.

Webpack’s execution process

#

Webpack begins its work from entries. Often these are JavaScript modules where webpack begins its traversal process. During this process, webpack evaluates entry matches against loader configurations that tell webpack how to transform each match.

Resolution process

#

An entry itself is a module and when webpack encounters one, it tries to match the module against the file system using the resolve configuration. For example, you can tell webpack to perform the lookup against specific directories in addition to node_modules.

If the resolution pass failed, webpack will raise a runtime error. If webpack managed to resolve a file, webpack performs processing over the matched file based on the loader definition. Each loader applies a specific transformation against the module contents.

The way a loader gets matched against a resolved file can be configured in multiple ways, including by file type and by location within the file system. Webpack’s flexibility even allows you to apply a specific transformation to a file based on where it was imported into the project.

The same resolution process is performed against webpack’s loaders. Webpack allows you to apply similar logic when determining which loader it should use. Loaders have resolve configurations of their own for this reason. If webpack fails to perform a loader lookup, it will raise a runtime error.

Webpack resolves against any file type

#

Webpack will resolve each module it encounters while constructing the dependency graph. If an entry contains dependencies, the process will be performed recursively against each dependency until the traversal has completed. Webpack can perform this process against any file type, unlike specialized tools like the Babel or Sass compiler.

Webpack gives you control over how to treat different assets it encounters. For example, you can decide to inline assets to your JavaScript bundles to avoid requests. Webpack also allows you to use techniques like CSS Modules to couple styling with components. Webpack ecosystem is filled with plugins that extend its capabilities.

Although webpack is used mainly to bundle JavaScript, it can capture assets like images or fonts and emit separate files for them. Entries are only a starting point of the bundling process and what webpack emits depends entirely on the way you configure it.

Evaluation process

#

Assuming all loaders were found, webpack evaluates the matched loaders from bottom to top and right to left (styleLoader(cssLoader('./main.css'))) while running the module through each loader in turn. As a result, you get output which webpack will inject in the resulting bundle. The Loader Definitions chapter covers the topic in detail.

If loader evaluation completed without a runtime error, webpack includes the source in the bundle. Although loaders can do a lot, they don’t provide enough power for advanced tasks. Plugins can intercept runtime events supplied by webpack.

A good example is bundle extraction performed by the MiniCssExtractPlugin which, when used with a loader, extracts CSS files out of the bundle and into a separate file. Without this step, CSS would be inlined in the resulting JavaScript, as webpack treats all code as JavaScript by default. The extraction idea is discussed in the Separating CSS chapter.

Finishing

#

After every module has been evaluated, webpack writes output. The output is a small runtime that executes the result in a browser and a manifest listing bundles to load. The runtime can be extracted to a file of its own, as discussed later in the book.

That’s not all there is to the bundling process. For example, you can define specific split points where webpack generates separate bundles that are loaded based on application logic. This idea is discussed in the Code Splitting chapter.

Webpack is configuration driven

#

At its core, webpack relies on configuration as in the sample below:

webpack.config.js

const path = require("path");

const webpack = require("webpack");

module.exports = {

entry: { app: "./entry.js" }, // Start bundling

output: {

path: path.join(__dirname, "dist"), // Output to dist directory

filename: "[name].js", // Emit app.js by capturing entry name

},

// Resolve encountered imports

module: {

rules: [

{ test: /\.css$/, use: ["style-loader", "css-loader"] },

{ test: /\.js$/, use: "swc-loader", exclude: /node_modules/ },

],

},

// Perform additional processing

plugins: [new webpack.DefinePlugin({ HELLO: "hello" })],

// Adjust module resolution algorithm

resolve: { alias: { react: "preact-compat" } },

};

Webpack’s configuration model can feel a bit opaque at times as the configuration file can appear monolithic and it can be difficult to understand what webpack is doing unless you know the ideas behind it. The book exists to make the concepts and ideas to address this problem.

entry can be a function and an asynchronous one even. At times, there are multiple ways to achieve the same, especially with loaders.

test, it will be evaluated first. See the Loader Definitions chapter to understand the different possibilities better.

Hot Module Replacement

#

You are likely familiar with tools, such as LiveReload↗ or BrowserSync↗, already. These tools refresh the browser automatically as you make changes. Hot Module Replacement (HMR) takes things one step further. In the case of React, it allows the application to maintain its state without forcing a refresh. While this does not sound all that special, it can make a big difference in practice.

Asset hashing

#

With webpack, you can inject a hash to each bundle name (e.g., app.d587bbd6.js) to invalidate bundles on the client side as changes are made. Bundle splitting allows the client to reload only a small part of the data in the ideal case.

Code splitting

#

In addition to HMR, webpack’s bundling capabilities are extensive. Webpack allows you to split code in various ways. You can even load code dynamically as your application gets executed. This sort of lazy loading comes in handy, especially for broader applications, as dependencies can be loaded on the fly as needed.

Even small applications can benefit from code splitting, as it allows the users to get something usable in their hands faster. Performance is a feature, after all. Knowing the basic techniques is worthwhile.

Webpack 5

#

Webpack 5 is a new version of the tool that promises the following changes:

- There’s better caching behavior during development - now it reuses disk-based cache between separate runs.

- Micro frontend style development is supported through Module Federation and you can learn more about it in the chapter.

- Internal APIs (esp. plugins) have been improved and older APIs have been deprecated.

- The development and production targets have better defaults. For example now

contenthashis used for production resulting in predictable caching behavior. The topic is discussed in detail at the Adding Hashes to Filename chapter.

Webpack 5 release post↗ lists all the major changes. Apart from the caching improvements and Module Federation, it can be considered a clean up release.

There’s an official migration guide↗ that lists all of the changes that have to be done to port a project from webpack 4 to 5.

It’s possible that a project will run without any changes to the configuration but that you’ll receive deprecation warnings. To find out where they are coming from, use node --trace-deprecation node_modules/webpack/bin/webpack.js when running webpack.

Conclusion

#

Webpack comes with a significant learning curve. However, it’s a tool worth learning, given how much time and effort it can save over the long term. To get a better idea how it compares to others, check out the Comparison of Build Tools appendix.

Webpack won’t solve everything. However, it does solve the problem of bundling. That’s one less worry during development.

To summarize:

- Webpack is a module bundler, but you can also use it running tasks as well.

- Webpack relies on a dependency graph underneath. Webpack traverses through the source to construct the graph, and it uses this information and configuration to generate bundles.

- Webpack relies on loaders and plugins. Loaders operate on a module level, while plugins rely on hooks provided by webpack and have the best access to its execution process.

- Webpack’s configuration describes how to transform assets of the graphs and what kind of output it should generate. Part of this information can be included in the source itself if features like code splitting are used.

- Hot Module Replacement (HMR) helped to popularize webpack. It’s a feature that can enhance the development experience by updating code in the browser without needing a full page refresh.

- Webpack can generate hashes for filenames allowing you to invalidate past bundles as their contents change.

In the next part of the book, you’ll learn to construct a development configuration using webpack while learning more about its basic concepts.