Introduction to React

#

Facebook’s React↗ has changed the way we think about web applications and user interface development. Due to its design, you can use it beyond web. A feature known as the Virtual DOM enables this.

In this chapter we’ll go through some of the basic ideas behind the library so you understand React a little better before moving on.

What is React?

#

React is a JavaScript library that forces you to think in terms of components. This model of thinking fits user interfaces well. Depending on your background it might feel alien at first. You will have to think very carefully about the concept of state and where it belongs.

Because state management is a difficult problem, a variety of solutions have appeared. In this book, we’ll start by managing state ourselves and then push it to a Flux implementation known as Alt. There are also implementations available for several other alternatives, such as Redux, MobX, and Cerebral.

React is pragmatic in the sense that it contains a set of escape hatches. If the React model doesn’t work for you, it is still possible to revert back to something lower level. For instance, there are hooks that can be used to wrap older logic that relies on the DOM. This breaks the abstraction and ties your code to a specific environment, but sometimes that’s the pragmatic thing to do.

Virtual DOM

#

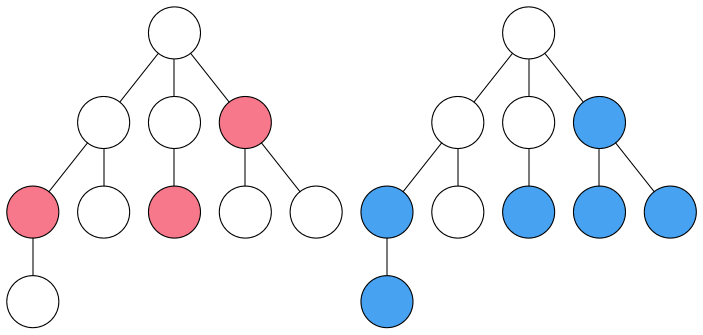

One of the fundamental problems of programming is how to deal with state. Suppose you are developing a user interface and want to show the same data in multiple places. How do you make sure the data is consistent?

Historically we have mixed the concerns of the DOM and state and tried to manage it there. React solves this problem in a different way. It introduced the concept of the Virtual DOM to the masses.

Virtual DOM exists on top of the actual DOM, or some other render target. It solves the state manipulation problem in its own way. Whenever changes are made to it, it figures out the best way to batch the changes to the underlying DOM structure. It is able to propagate changes across its virtual tree as in the image above.

Virtual DOM Performance

#

Handling the DOM manipulation this way can lead to increased performance. Manipulating the DOM by hand tends to be inefficient and is hard to optimize. By leaving the problem of DOM manipulation to a good implementation, you can save a lot of time and effort.

React allows you to tune performance further by implementing hooks to adjust the way the virtual tree is updated. Though this is often an optional step.

The biggest cost of Virtual DOM is that the implementation makes React quite big. You can expect the bundle sizes of small applications to be around 150-200 kB minified, React included. gzipping will help, but it’s still big.

React Renderers

#

As mentioned, React’s approach decouples it from the web. You can use it to implement interfaces across multiple platforms. In this case we’ll be using a renderer known as react-dom↗. It supports both client and server side rendering.

Universal Rendering

#

We could use react-dom to implement so called universal rendering. The idea is that the server renders the initial markup and passes the initial data to the client. This improves performance by avoiding unnecessary round trips as each request comes with an overhead. It is also useful for search engine optimization (SEO) purposes.

Even though the technique sounds simple, it can be difficult to implement for larger scale applications. But it’s still something worth knowing about.

Sometimes using the server side part of react-dom is enough. You can use it to generate invoices↗ for example. That’s one way to use React in a flexible manner. Generating reports is a common need after all.

Available React Renderers

#

Even though react-dom is the most used renderer, there are a few others you might want to be aware of. I’ve listed some of the well known alternatives below:

- React Native↗ - React Native is a framework and renderer for mobile platforms including iOS and Android. You can also run React Native applications on the web↗.

- react-blessed↗ - react-blessed allows you to write terminal applications using React. It’s even possible to animate them.

- gl-react↗ - gl-react provides WebGL bindings for React. You can write shaders this way for example.

- react-canvas↗ - react-canvas provides React bindings for the Canvas element.

React.createElement

and JSX

#

React.createElement

and JSX

Given we are operating with virtual DOM, there’s a high level API↗ for handling it. A naïve React component written using the JavaScript API could look like this:

const Names = () => {

const names = ['John', 'Jill', 'Jack'];

return React.createElement(

'div',

null,

React.createElement('h2', null, 'Names'),

React.createElement(

'ul',

{ className: 'names' },

names.map(name => {

return React.createElement(

'li',

{ className: 'name' },

name

);

})

)

);

};

As it is verbose to write components this way and the code is quite hard to read, often people prefer to use a language known as JSX↗ instead. Consider the same component written using JSX below:

const Names = () => {

const names = ['John', 'Jill', 'Jack'];

return (

<div>

<h2>Names</h2>

{/* This is a list of names */}

<ul className="names">{

names.map(name =>

<li className="name">{name}</li>

)

}</ul>

</div>

);

};

Now we can see the component renders a set of names within a HTML list. It might not be the most useful component, but it’s enough to illustrate the basic idea of JSX. It provides us a syntax that resembles HTML. It also provides a way to write JavaScript within it by using braces ({}).

Compared to vanilla HTML, we are using className instead of class. This is because the API has been modeled after the DOM naming. It takes some getting used to and you might experience a JSX shock↗ until you begin to appreciate the approach. It gives us an additional level of validation.

Conclusion

#

Now that we have a rough understanding of what React is, we can move onto something more technical. It’s time to get a small project up and running.