Unexpected - The Extensible BDD Assertion Toolkit - Interview with Sune Simonsen

When it comes to testing, often you assert certain truths. At the very least you might have simple asserts↗ sprinkled in your code. Or you might push them to separate suites which you then execute using a test runner.

Unexpected↗ by Sune Simonsen↗ takes this simple idea into a little different direction. Read on to learn more.

Can you tell a bit about yourself?

#

I don’t consider my personal life that exciting - or at least it is pretty far from your regular JavaScript hacker trying to start the next unicorn business from a dorm room. I am a family man with two small girls and a wife. We live a pretty regular and happy life in Copenhagen.

I started my career as an enterprise Java consultant, after doing that for five years I saw the industry starting to take a turn towards the front-end being the orchestrating part in most applications. So I decided to change my career and focused on the front-end - that was one of the best decisions I have ever made.

Soon after this change, I started working at One.com. A great thing about working there was that it had a small team consisting of very talented people in charge of building most of their web applications. It was quite a large scale, and we had a lot of technical freedom, so I learned a lot from working there.

Little more than a year ago I switched jobs to Zendesk where I’m currently building React applications backed by GraphQL. So far my journey with Zendesk has been incredible, it is a great company with so many fantastic people. Zendesk is moving fast, so it is also a lot of fun to be a passenger on this bullet train.

How would you describe Unexpected to someone who has never heard of it?

#

Unexpected is an assertion library like Chai↗ or expect.js↗. It can be used with any test runner that catches exceptions, but I would recommend Mocha↗, Jest↗ or Jasmine↗ as Unexpected is integration tested with these runners on every release.

Below you can see an example of a test written with Mocha and Unexpected where we assert that the indexOf method on arrays returns -1, when it can’t find the given element.

const expect = require('unexpected')

describe('Array', () => {

describe('indexOf', () => {

it('should return -1 when the given item is not present',

() => {

expect([0, 1, 2, 3].indexOf(4), 'to equal', -1)

}

)

})

})

Why did you develop Unexpected?

#

When I came to One.com, there were no tests for the front-end, so I started introducing a test setup. We were using expect.js↗ as our assertion library and were happy with it. One of my colleagues started using expect.js for some randomized tests, and it happened to be very slow.

I investigated the performance issue and found that every expect would create 84 Assertion instances. In an attempt to impress my colleague, I hacked together the first version of Unexpected that was just a function backed by a hash table of assertions.

That version was as capable as expect.js, but a lot faster. The idea that made this possible was to use strings as assertions, instead of the method chains that expect.js uses. The following code snippet contrast the syntax of expect.js with Unexpected.

// expect.js

expect(42).to.be.within(0, Infinity)

// Unexpected

expect(42, 'to be within', 0, Infinity)

My team embraced the project and started using it for all JavaScript testing. That meant the library was improved based on real use cases as they appeared. Unexpected owes a lot to my former colleague at One.com, especially Andreas Lind↗.

How does Unexpected work?

#

After almost four years of development Unexpected’s implementation looks very different from the initial solution, we introduced custom assertions, a plugin API, an extremely flexible dynamic type system that allow you to namespace assertions by type, asynchronous assertions, colored output and error diffing in a way you have never seen before.

We still have an assertion lookup table, but as you can reuse the same assertion for several types, the lookup table maps to a list of assertions ordered by precedence. We look up the assertion string, find the first assertion that has a matching type signature and execute it. Below you can see an example of the same assertion string on two different types:

// Expect that a string contains two sub-strings

expect('Hello beautiful world!', 'to contain', 'Hello', 'world')

// Expect that an array contains two items

expect([0, 1, 2], 'to contain', 0, 2)

When you run the above code snippet, two different assertions will be called as the types differ.

Built with Extensibility in Mind

#

Unexpected is build with extensibility in mind from the ground up. All of the built-in assertions and types are installed as plugins. All assertions are defined by delegating to others except for one. I find this to be a very elegant solution.

As an example, the assertion to be true is defined the following way:

expect.addAssertion('<boolean> [not] to be true',

(expect, subject) => {

expect(subject, '[not] to be', true)

}

)

Output Through MagicPen

#

Another implementation detail that might be interesting is that all output generated by Unexpected is created with a library that I wrote called MagicPen↗. The cool thing about MagicPen is that you append to a buffer, which has a very flexible API. It allows us to create very complex output quickly.

Because we append the output to a buffer in a high-level format, we can serialize the output to both plain text, ANSI colored text, and HTML.

Below you can see some output from an Unexpected error message generated by MagicPen:

A lot of the output we generated with Unexpected would just be too hard without MagicPen in my opinion.

How does Unexpected differ from other solutions?

#

Unexpected differ from other assertion libraries in a very obvious way by using a different syntax than all other assertion libraries I have seen. Using assertion strings was a coincidence that turned out to be fantastic.

Strings Instead of Method Chaining

#

A lot of people get turned off by the different approach, but I think that it mainly comes down to familiarity. There are a lot of advantages of using strings instead of method chaining. We can display a helpful error message when you mistype something:

We can use assertion strings when adding new assertions:

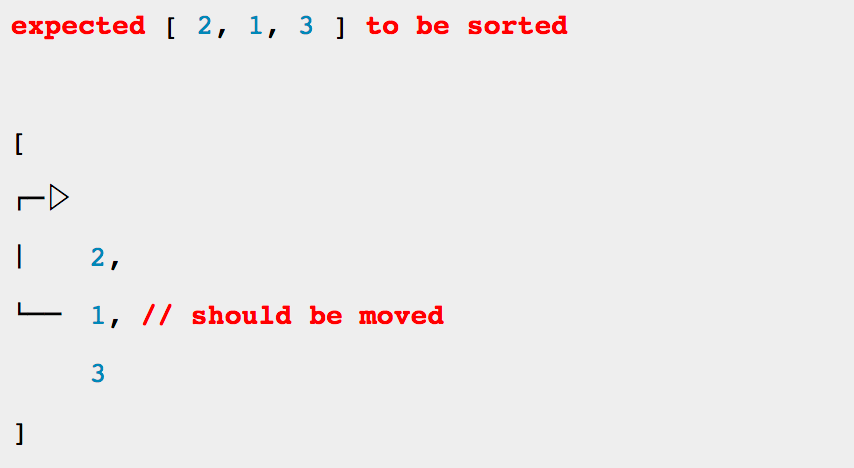

expect.addAssertion('<array> [not] to be sorted',

(expect, subject) => {

expect(subject, '[not] to equal', [].concat(subject).sort())

}

)

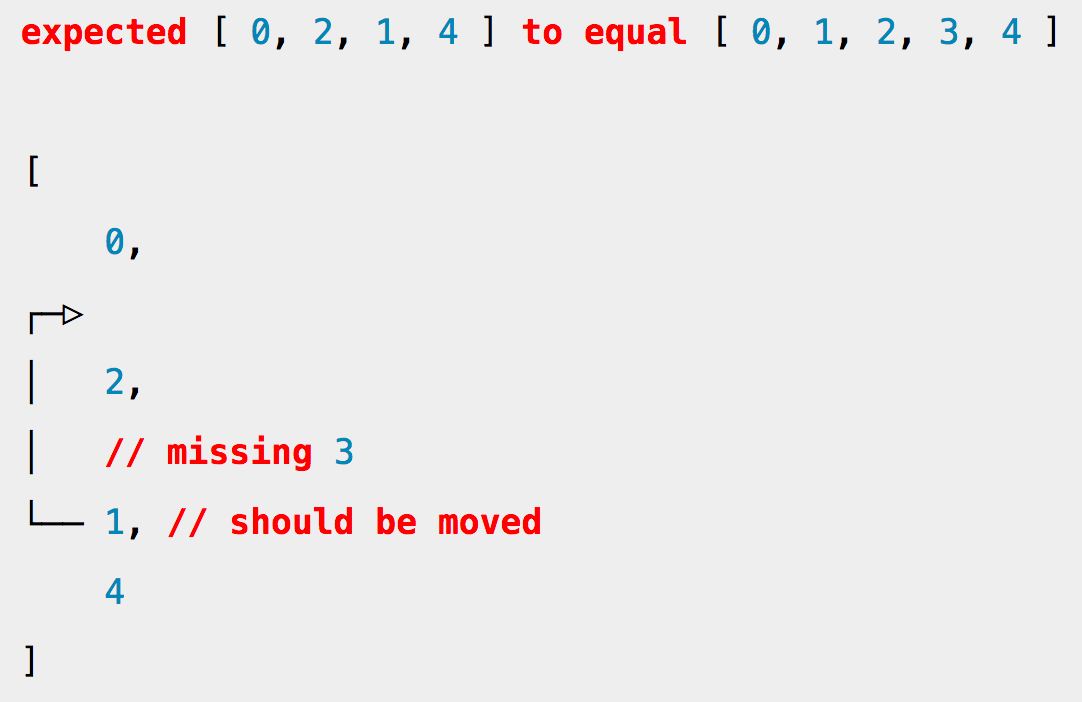

Because we know your assertion we can generate a nice default error message for an assertion like this:

expect([2, 1, 3], 'to be sorted')

And here’s the resulting message:

Faster Assertions and Colored Output

#

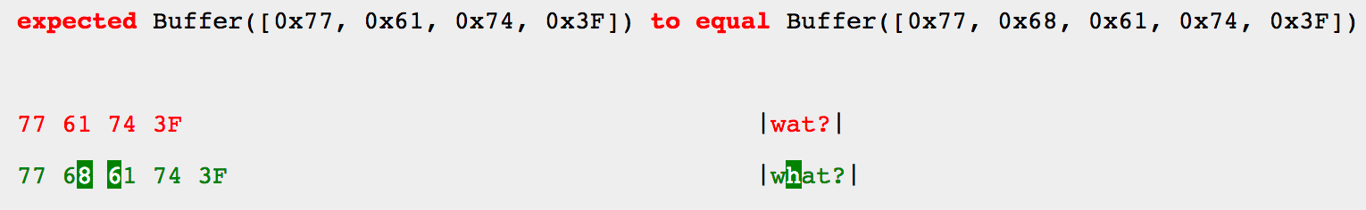

Unexpected allows faster assertion lookup than a chained API due to its approach. Another thing that sets us apart from the rest of the assertions libraries is that we offer very specific colored output. Below you can see the output when comparing two buffers:

Plugin API

#

We offer a much more powerful plugin API than other assertion libraries, that enables plugin authors to create support for new types and tools that we never planned.

An example of that is the excellent unexpected-react↗ plugin from Dave Brotherstone↗ that enables you to test React components in a declarative way and gives you very detailed errors when things fail.

Below you can see an error message from unexpected-react:

Asynchronous Assertions

#

Finally Unexpected has first class support for asynchronous assertions. You can even combine multiple asynchronous assertions.

Below is an example showing a test that combines multiple asynchronous assertions. The test asserts that a Node.js readable stream outputs an image that’s at most 10% different from a reference image and have the format png:

const fs = require('fs')

const expect = require('unexpected').clone()

.use(require('unexpected-stream'))

.use(require('unexpected-image'))

.use(require('unexpected-resemble'))

it('should spew out the expected image', () => (

expect(

fs.createReadStream('foo.png'),

'to yield output satisfying',

expect.it('to resemble', 'bar.png', {

mismatchPercentage: expect.it('to be less than', 10)

}).and('to have metadata satisfying', {

format: 'PNG'

})

)

))

The cool thing is that you can choose how advanced you want to go, Unexpected won’t stop you.

What next?

#

That is a splendid question. I feel like we have most of the features I would like by now, in my opinion, the energy should be put into improving the plugins. A lot of the contributors are meeting in Copenhagen in February to discuss how we continue to progress the library - so it going to be interesting what comes out of that.

What does the future look like for Unexpected and web development in general? Can you see any particular trends?

#

I don’t consider Unexpected to be especially aimed at web development but see it more as a general purpose assertion library that can be used to test any JavaScript code base.

Where I see Unexpected shine, is that it can be adapted to any code base by creating new plugins. You see a lot of assertion libraries tailored to testing JSX components, but then you need a new library when the trend changes.

Optional Typing is Getting Traction

#

I currently following the optional typing trend like Flow↗ and TypeScript↗ with a bit of skepticism - but it seems to be getting a lot of traction. I think this movement will be a stepping stone towards stricter languages like Reason↗, Elm↗ or even PureScript↗ as people realize the trade-offs these halfway safe type systems provides.

Still Work to Do

#

I have a strong feeling that we haven’t arrived at the perfect development tool-chain yet - React and friends have solved a lot of problems that was a huge struggle in the past. But this new world where people remix their platform with crazy metaprogramming achieved trough transpiling has to stop at some point.

My guess is that we will see something like Reason↗ being able to eliminate dead code in a much better way than any dynamic language and therefore provide much better download sizes. That might be the tipping point that will make the masses switch.

What advice would you give to programmers getting into web development?

#

Use your brain to evaluate new things you bring into your stack, don’t just follow the hype blindly. You don’t have to switch your approach to how you handle CSS every week just because your Twitter stream indicate that is the way it should be done.

When you create a side-project, decide upfront if you want to learn something new or want the project to succeed - you can’t have both.

Use a queue instead of a stack in your brain to handle incoming side-projects - that is how you get something done. This advice was stolen from Andreas Lind↗, but it is the best advice I ever received.

When you run into problems with a library, make it a habit of contributing. You will realize that you can get fixes approved for most projects.

Surround yourself with people that are better than yourself. If you think you better then your co-workers, it is time to leave.

Who should I interview next?

#

Andreas Lind↗ or Mathias Buus↗ they are both wizard level Danish JavaScript hackers.

Any last remarks?

#

Stay happy; it is only bits.

Conclusion

#

Thanks for the interview Sune! I think it’s particularly impressive that you ended up with a nice, fluent plugin API. I’m a great fan of plugin based systems myself and even though they require some upfront investment and design, they are often worth it if you value flexibility. Particularly the quality of output seems to set Unexpected apart.

To learn more, check out the site of Unexpected↗. You can also find Unexpected↗ and MagicPen↗ on GitHub.